Mary Eleanor Bowes

Mary Eleanor Bowes was the great-great-great-great-grandmother of the Queen. A contemporary of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, Mary had a dramatic life which has been told in several books, but as I read them, I was gripped by a sense that she has had a very raw deal, not only because of what happened to her, but in posterity. Much of what has been written about Mary Eleanor is based on the Confessions, which she wrote under enormous duress whilst married to a violent and abusive husband. In order to control her, and more importantly her fortune, he conducted a campaign to ruin her reputation, with the intention of isolating her from anyone who might have helped. The ways in which he did this are horribly fascinating, and included commissioning revolting caricatures for publication in the newspapers. (I was reminded of this in the recent coverage of the divorce of Charles Saatchi and Nigella Lawson.)

Gillray cartoon courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery under Creative Commons License

The first time I visited Gibside, I was intrigued by the guide's stories about Mary Eleanor. Wanting to know more, I bought Wedlock, then the other, less attractively-presented versions: ‘The Trampled Wife: the scandalous life of Mary Eleanor Bowes’ (2006) and ‘The Unhappy Countess’ (1957). These three accounts left me with so many questions, so many contradictory impressions and such a sense of injustice that I decided to dig more deeply by reading some of the original sources on which so much of her reputation rests.

Mary Eleanor Bowes was an intelligent, accomplished, classically-trained multi-linguist, a cultured and liberal polymath whose education, thanks to an enlightened and doting father, was extremely unusual in a woman of the eighteenth century. She was acknowledged as an eminent female botanist, and the late eighteenth century was a time of marvels in the world of botany: expeditions, some of which she sponsored, brought back previously-unimagined plants and seeds from Australia and South Africa: the Orangery was built to house her specimens.

Photograph of the Orangery by Tracey Ann Mayor

It seems to me that the negative aspects of Mary Eleanor’s reputation have entirely swamped the positive, and two documents are central to the reasons for that: her own ‘Confessions’ and the account written by the obsequious and two-faced doctor, Jesse Foot. The fact that ‘Confessions’ was written under the most severe duress and was probably largely dictated by her abuser is sometimes acknowledged but largely overlooked. Jesse Foot waited until both his subjects were dead before he sold his story, entitled ‘The Lives of Andrew Robinson Bowes Esq., and the Countess of Strathmore, written from Thirty-Three Years Professional Attendance, from Letters and other Well-Authenticated Documents.’

Like many abusers, Stoney Bowes succeeded in isolating his victim: he bullied, manipulated, lied, bribed, bought shares in newspapers in which to publish articles and cartoons with the specific purpose of ruining her reputation. When Mary Eleanor finally found the means, motivation and strength to escape, she proved herself to be unbelievably resilient, determined and resourceful, and she suddenly found she was able to draw on the longstanding loyalty of servants, tenants, estate workers and miners, who at one point surrounded Streatlam in an effort to rescue her from her abductors. One of the people who finally rescued her by knocking Stoney Bowes from his horse was an estate-worker from Gibside called Gabriel Thornton. That little detail, a working man with the name of an angel, sparked my imagination.

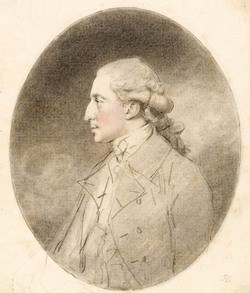

Portrait of Andrew Stoney Bowes by John Downman in 1781.

Reproduced courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, under Creative Commons

And here is the heart of my purpose: my Mary Eleanor is a woman the reader can care about, admire and root for. She tells the story in the first person, looking back over her life, so right from the start you are invited to enter her mind. When she makes mistakes, as she often does, you will understand why she made them. Her core is a deep and abiding love of the natural world, and especially of Gibside. And Gibside, embodied in that devoted worker named Gabriel, loves her.

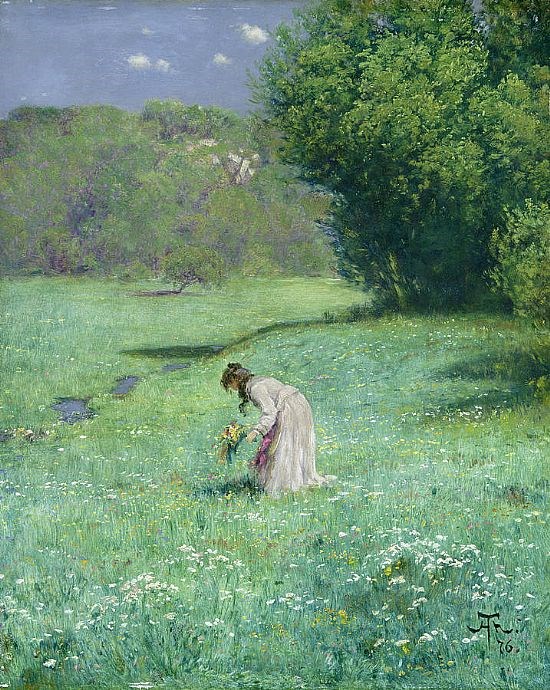

Woodland Meadow by Hans Thoma (Creative Commons)

The beauty of reading and writing fiction is freedom: freedom to enter other lives and times and take an imaginative journey. When that journey takes place in a setting you know, it is all the more inspiring. The oldest trees at Gibside are a pair of oaks by the river, so one very tender and significant scene takes place there. A conversation with her mother in the wake of her father’s death is set in the house, and the sounds of the chapel being built can be heard across the green. She remembers accompanying her father on a visit to the workers building the column when she was six years old: it was the moment when she first made friends with Gabriel.

Liberty and the Moon by Tom Carr

Liberty is central to the themes of the novel: not only because of Gibside's statue but also the fact that while Mary Eleanor struggled for personal freedom, the American War of Independence and the French Revolution were taking place in the background. Her courage in achieving a divorce in that unashamedly misogynistic period, when a judge could rule that a man was free to beat his wife with a stick no thicker than his thumb, should not be forgotten.

It was exceptionally difficult to choose a title: among the ones I considered were A Heart of Oak, The Countess and the Conman and Lady Liberty. I kept coming back to My Name is Eleanor because of its simplicity and directness: she was known as many things in the course of her eventful life, but this is the story she might have told.